Malware-as-a-Smart-Contract – Part 1: Weaponising BSC to Target Windows Users via WordPress

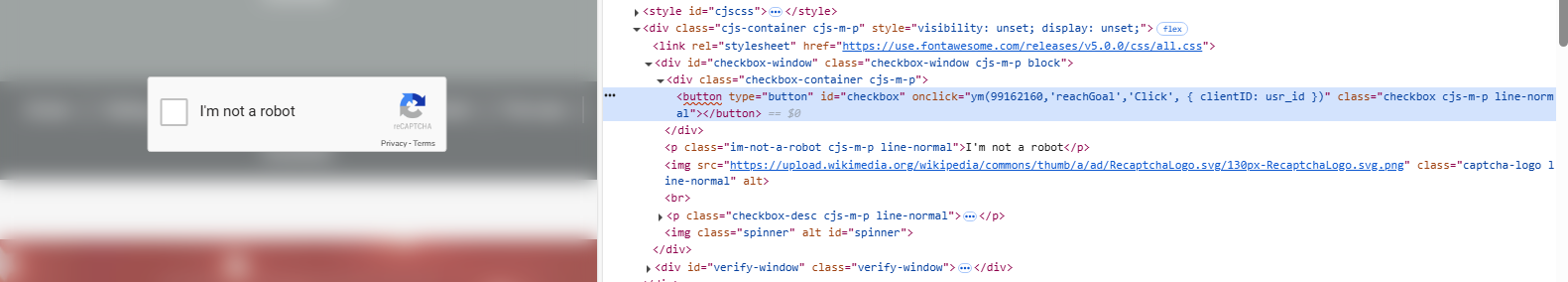

A few weeks ago, I found an interesting ClickFix sample (e.g., a fake reCAPTCHA) during an investigation of a compromised WordPress website. A threat actor is infecting legitimate WordPress website...